Few films in recent memory have tapped zeitgeist angst like Ramin Bahrani’s 99 Homes. Set in Orlando Florida, the hot-button Oscar contender tells of blue collar everyman Dennis Nash (Andrew Garfield) and the devil he must deal with when he goes to work for the very man who evicted him from his family home, bank-backed real-estate heavy Rick Carver (Michael Shannon). A true auteur with two highly acclaimed works to his credit (Goodbye Solo, 2008; At Any Price, 2012), Bahrani’s story confronts the crumbling society that is the ‘New America’, where the men and women whose spirit forged the nation are fodder for big business profiteers on an unprecedented scale. During his visit in June for the Sydney Film Festival screening of 99 Homes, Bahrani spoke with SCREEN-SPACE about the social imbalance and human cost that inspired his latest drama…

The eviction scenes are some of the most wrenching movie moments in 2015…

As a filmmaker, you have to see the film so many times to finish it. And then you watch it with audiences, which I did first at Venice then Toronto then Sundance. But, to this day, the Nash eviction and the eviction of the old man are still so hard to watch. When I was researching, I was present for the eviction of an old man who was also suffering dementia, and it was horrible. For the Nash eviction, I had our incredible production designer, Alex DiGerlando, completely empty then re-set the house, and the great cinematographer, Bobby Bukowski lit it from the outside, so that there was nothing that would be in the way of the cast. The actors knew that they had freedom, within any scene, to add and subtract dialogue, just to be in the moment. We shot with two cameras, for simplicity. We hired a real sheriff and real clean-out crews, who had done evictions, and we just let them loose. And I edited it as if it was a 10 minute rape scene; totally raw, emotional, visceral.

Michael Shannon’s Rick is a hyena, the new alpha-predator, picking at the bones of the dying American middle-class…

Michael Shannon’s Rick is a hyena, the new alpha-predator, picking at the bones of the dying American middle-class…

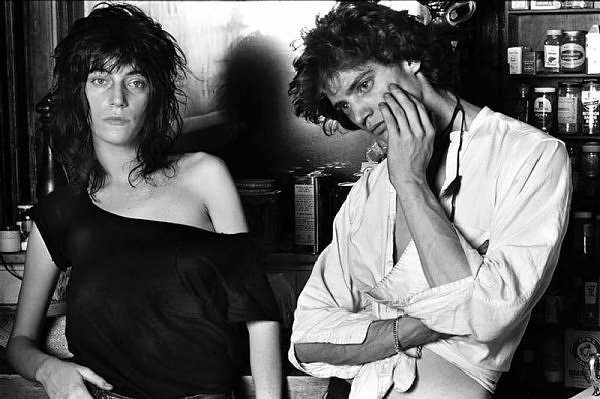

That’s right. After the Sundance screening, I wanted to change a couple of minor things, which most filmmakers almost never get the opportunity to do. I wanted to use a different shot of Michael at the end of the film, when he’s got his sunglasses back on. It looks as if he is even more in control, like the sheriffs and the police are merely his servants. (Pictured, right; co-stars Andrew Garfield and Michael Shannon).

And he barks one of the year’s best lines, “America doesn’t bail out losers, it bails out winners.”

A quick story that I’ve never told anyone and that I swear is true. I was at a point in the writing where I knew Michael needed a ‘big speech’ moment, but it had to be integral to the story, drawing in Andrew’s character even deeper. But I couldn’t figure out how to do it; for two weeks I struggled with the dialogue. I had the moment; I knew when it had to be, but not what words had to be used. I couldn’t figure how to do it and by now, it is the 4th of July, the day we all celebrate America becoming what it is today. And, I swear, I thought of the words on that day. I left the fireworks and wrote the scene with the fireworks in the background (laughs). It was crazy!

Were you cautious of ‘Rick Carver’ not becoming a ‘Gordon Gekko’-like beacon for this ruthless capitalism? Of his actions becoming heroic, even iconic to the wealthy, like Michael Douglas’ character did?

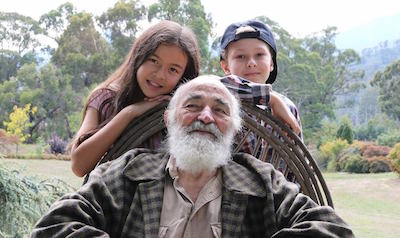

In some ways, he is the new Gekko. And I think Michael makes it a little more shaded. I’ve told Oliver Stone that Wall Street was a big influence on this film. If you listen to Gordon Gekko very carefully, he talks about his blue-collar background, his electrician Dad who had a heart attack, how he didn’t have an Ivy League future lined up for him like all the other rich kids. A pivotal moment is when Michael tells Andrew about Rick’s upbringing, living on construction sites and how his father had a bad fall and was screwed by the system. It becomes hard to argue with Michael sometimes. He says, “You did honest, hard work your whole life and what did it get you but me knocking on your door?” He’s right. Michael and I talked a lot about what his characters upbringing must have been like, how hard it would have been. He’s just a dad who is not going to let it happen to him and his kids. I don’t think his behaviour is correct, but it is hard to judge him. I like that the film has some moral ambiguity. (Pictured, above; Bahrani on-set with Michael Shannon).

In some ways, he is the new Gekko. And I think Michael makes it a little more shaded. I’ve told Oliver Stone that Wall Street was a big influence on this film. If you listen to Gordon Gekko very carefully, he talks about his blue-collar background, his electrician Dad who had a heart attack, how he didn’t have an Ivy League future lined up for him like all the other rich kids. A pivotal moment is when Michael tells Andrew about Rick’s upbringing, living on construction sites and how his father had a bad fall and was screwed by the system. It becomes hard to argue with Michael sometimes. He says, “You did honest, hard work your whole life and what did it get you but me knocking on your door?” He’s right. Michael and I talked a lot about what his characters upbringing must have been like, how hard it would have been. He’s just a dad who is not going to let it happen to him and his kids. I don’t think his behaviour is correct, but it is hard to judge him. I like that the film has some moral ambiguity. (Pictured, above; Bahrani on-set with Michael Shannon).

Which further complicates the ‘good guy/bad guy’ dynamic of 99 Homes...

There are movies that utilise characters for pure villainy, and classic characters like Iago, and those characters exist in real life. I don’t think the modern world should exclude them, and I think the modern world is too quick to psychologise them away. Here, the real villain is the system and that is something that we are struggling with globally, to varying degrees. We are confronted by a system created by the wealthy that seems to protect and increase their wealth. What on earth is ‘capital gains tax’ or ‘inheritance tax’? Why does buying a home in America save you money on taxes? On both sides of the political spectrum, from post-World War 2 but specifically from 1979 to today, laws have been created that have made the rich richer and made the middle class struggle even harder. This is not an agenda-driven film, but one that goes to the emotionality of that situation.

Is 99 Homes an exercise in introspection? Is it an attempt to redefine the America of today?

Is 99 Homes an exercise in introspection? Is it an attempt to redefine the America of today?

More reflect than redefine. All my films have this humanist, social bent to them. When I went to Florida, I found a place where everybody carried a gun and there was mind-boggling corruption. Everything you see in the film is researched and real. The guy played by Clancy Brown in the film, who ran that foreclosure mill, is all real, was [responsible] for endless forgeries. He never went jail; took his company public, sold it to the Chinese for billions, took his money and took off. Structurally, I was able to create this Faustian thriller but from a very humanist perspective. I’m happy to be able to inject a little humanism into what is essentially a very mainstream thriller, crafting something that inspires conversation as well as telling a solid, thrilling narrative. (Pictured, right; Andrew Garfield as Dennis Nash).

The idealism of Frank Green, the stoic character superbly played by Tim Guinee, who takes an immovable stand against the system, is so crucial to that humanism.

There is something in the Frank Green character that inspires Nash and, in turn inspires me to do that kind of behaviour. Even when you know that your individual action can’t overwhelm the system, you know you have to do it anyway. There are those real-life heroes, like Martin Luther King or Gandhi, who have a massive impact; those people who have stood and said, as Frank puts it in the film, “The sun is shining and no one is going to tell me otherwise.” And suddenly a country changes. That’s amazing.

99 Homes will be released on November 19 in Australian cinemas by Madman Entertainment; it is currently screening in select cinemas in the US and UK.